Background

When the Secretary of State for the Coalition Government announced, in 2010, the creation of Free Schools and subsequently invited proposals from groups with innovative and creative ideas, the seeds were sown for a new provision among some of the co-operators with a history of working within the Marches Consortium and the subsequent co-operatives. The stalemate that had followed the end of both the national TVEI Pilot and Extension Projects, together with the drying up of more local and regional funding for projects such as Alternative Learning Pathways to Success (ALPS), linked to a clear change in local authority culture, worried many educational professionals.

There had developed an inward-looking attitude, one favouring retrenchment and survival set in a context of a central government push to elitist academic success provision. This had led directly to a deep sense of community frustration that many groups of 14-19-yearold students were now receiving a bad deal and, in so doing, were accumulating problems for society into the future. Their choices had the academic system had become heightened and levels of achievement were falling.

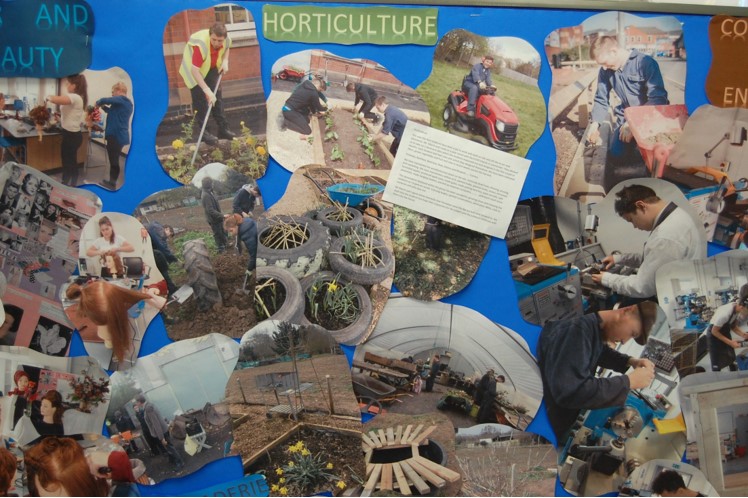

The number of students not in education, employment or training in Herefordshire (NEET) was at a worryingly high level when compared with the rest of the West Midlands and, at the time, anecdotal evidence indicated high levels of non-attendance, disaffection and alienation linked to complex social, learning and behavioural needs. Even in those early days, the stories of significant numbers of young people outside the system and sleeping under hedges, in barns and shop doorways had begun to stir the consciences of those who cared. The need for this form of highly specialised provision in the designated area had been proven since 1983 through the TVEI Pilot Project in Herefordshire with a dedicated Technical and Vocational 14-19 Centre, the TVEI Extension Project with its innovative work on 14-19 curriculum progression and continuity, the Robert Owen Group’s Vocational, Training and Educational Opportunities (VETO) Project and the Robert Owen Group’s Europeanfunded ALPS Project. Since the ALPS project ended in 2009 there had been no dedicated provision for this type of vocational learning, which was evidenced by a corresponding increase in the number of young people not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET).

The State of Herefordshire 2011 Report Additionally, the State of Herefordshire 2011 Report identified that employers found many young people to be poorly prepared for entering employment and that skilled trade vacancies were hard to fill. The following areas were specifically identified as threats and challenges to the local economy:

- Skilled trade occupations accounted for a relatively high proportion of those in employment; employers found skilled trade vacancies hard to fill and skilled trade vacancies accounted for the highest proportion of skill shortage vacancies.

- Employers reported that there were skills gaps in managerial and skilled trade occupations and that some young people were poorly prepared for work.

- There was still demand for migrant labour in Herefordshire that employers reported would be difficult to obtain from other sources.

- Herefordshire was losing approximately 5% of its working-age population, who travelled to work outside the county. Unemployment was higher than prior to the recession, particularly amongst people under the age of 25 and work-based earnings were low when compared both regionally and nationally, with the gap increasing. This gap in earnings was due to the dominance of lowtechnology manufacturing and low-value sectors of employment, such as agriculture and retailing, in the area.

- The gap in attainment between the best and worst performing areas at GSCE was still increasing, and there were more areas listed amongst the most deprived in England in terms of achievement in education and skills. Therefore, in one of the most rural areas of England there was a critical shortage of specialised pre-vocational and vocational education and training for the 14-19+ age group.

The aim of the Robert Owen Academy was to motivate and educate this growing population to realise the benefits of vocational training, work (including self-employment) and living and contributing to their communities as integrated and fully functioning citizens. The 14- 19+ Robert Owen Academy could tackle headon the challenge of maximising the number of young people in education and training whilst raising the whole profile of vocational education and training across the full ability range. It was to have as its core mission the challenge of the ‘parity of esteem’ between the academic and the vocational curricula.

The full story is described in the Evaluation Report – An Innovative School Ahead of Its Time – The Story of a Free School Journey from Concept to Closure. The final decision, taken on 8th March 2018 by the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the School System, to close the Robert Owen Academy on 31st August 2018 marks yet another landmark in the long struggle to develop vocational education in England. The letter indicated that the decision was driven by reasons of finance, but during the six years of uncertainty that central Government has created around the Academy, the reasons given for potential closure have shifted from poor OfSTED outcomes to a shortfall in recruiting, to opposition from the Local Authority, to financial difficulties.

The Trust remains uncertain as to the main driving force for closure, which has hung over our collective heads like the sword of Damocles since approval in July 2012. However, the view is emerging that either the Regional Schools Commissioner (RSC) or the Department for Education (DfE), or a combination thereof, encouraged by the Herefordshire Local Authority, wanted to reduce the capacity in Herefordshire and had alighted upon the Robert Owen Academy as the convenient sacrifice. Quite clearly, the motivation has shifted and changed over time and few of us have been able to detect any clarity to the reasoning. Without exception, it is agreed outside the magic circle of regional and national decision makers that those with the power wilfully refuse to understand what the Academy did and tried to do differently. When confronted, the power brokers return to their concept of a ‘bogstandard comprehensive school’, which the Robert Owen Academy has never pretended to be.

In short, we contend that although the Secretary of State has every right to withdraw our funding (providing legal process is followed), the decision making about our future has been poor and badly managed. We believe that the Free Schools Initiative, as originally conceived, was a brave attempt to bring about change in an English education system that has historically been highly resistant to change. The brave words and vision of the 1944 Education Act and subsequent engines for change have never brought about the required improvements that our young people desperately need. One size fits all never has and never will serve the highly individualistic needs of our students.

When, in the autumn of 2011 we set out to develop a consensus for change in the Marches sub region, which we hoped would lead to a firm 14-19 vocational education proposal, we listened to employer after employer who told us quite clearly that the school leaving product was not fit for purpose. In short, they needed the foundations for life, work and further learning, which are built out of knowledge, skills and experiences. The pioneers of the drive for the Academy knew that there were some things which couldn’t be changed in the short term and which would hold us back:

- The National Curriculum and the changes planned by the Secretary of State.

- The national fixation with examinations at 16 – namely GCSE and, increasingly, A level.

- The obsession in schools with meeting examination targets within the context of OfSTED criteria.

- The reluctance of head teachers to transfer or share students because of the impact of formula funding.

- The rapid growth in the number of students with complex needs, who were being gently steered out of many high schools.

- The centrality of the end of Key Stage 3 as a decision-making point in our young people’s lives, which should lead to opportunities to combine academic and vocational qualifications and meaningful work-based options within programmes tailored to each student’s aptitudes, abilities and preferences.

- The implicit academic elitism in our English education system which creates, by intent, an anti-vocational education society. The parity of esteem issue is one that any emerging 14-19 vocational academy would have to tackle head-on.

So, at one level we have palpably failed because the Secretary of State, through the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the School System, says so. However, if we as a country are to move on and face the challenges of a post Brexit society, set in the context of a rapidly globalising world, where technology will continue to transform our lives, we must learn the lessons from the Robert Owen Academy. The external challenges will not go away, in fact, by all predictions they will speed up with potentially devastating impacts on our country and our people. For those of us involved in the Robert Owen Academy and of grey hair and advanced years, we had expected a detailed evaluation of the Free Schools Project, just as we have approached virtually every education initiative since 1944 but, sadly, nothing has been forthcoming. It is almost as if the clutch of initiatives such as Free Schools, Studio Schools and UTCs are seen as a collective failure in the depths of Westminster, to be buried hastily and without ceremony. As a result, the Robert Owen Academies Trust has decided that it is our collective responsibility to produce an evaluation of what we did, what we tried to do, what worked, what failed, what pressures we were under and, in so doing, celebrate the changes we have made to the lives of over 300 students in our innovative school, which was ahead of its time.