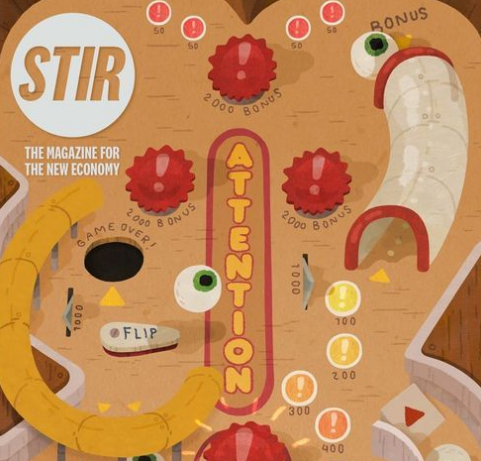

by Inez Aponte, illustration by Seb Westcott

In a letter to Joë Bousquet, the French philosopher Simone Weil wrote, “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity”. At the time, April 1942, there was no such thing as an ‘attention economy’. In the grip of war, attentions and economies were focused on the fulfilment of our immediate and fundamental needs for security and subsistence.

It wasn’t until 1971 that the first rumblings of what we have come to know as the attention economy can be found in the work of Nobel Prize winning economist Herbert Simon. Observing the advance of “an information-rich world”, he noted: “What information consumes is […] the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.”

It is interesting to note the opposition between the emphasis on generosity in Weil’s statement and “attention as a scarce resource” that Simon observed in the early 1970s. Though both statements indicate that attention is something of great value, what purpose this attention serves differs starkly.

For Weil, attention is an intensely relational act, reaching out towards another human. It expresses something of the word’s etymology, originating from the Latin attendere – ‘to give heed to,’ literally ‘to stretch toward’ – and shares its root with the verbs ‘to tend’ and ‘to attend’, meaning to take care of and be present at. She seems to be speaking of attention as a form of tending to a person or an object and in doing so both acknowledging and bestowing value. In contrast, Simon’s observation signals a warning: ‘Stocks’ of attention are limited and must be allocated “efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.”

Unfortunately, it is the words of our economists rather than our philosophers that have been heeded.

Over the last two decades, in fierce competition for the dollars that our attention represents, tech entrepreneurs have been designing ever more sophisticated ways to get inside our heads and direct our clicks towards the ‘pay now’ button. With the goal of keeping us online for as long as possible, they have been tracking our behaviour, gathering data points, and predicting our next move. Some would say they know us better than we know ourselves.

Facebook’s AI hub ingests trillion of data points every day, making six trillion behavioural predictions every second. In 2017, a leaked document, based on research quietly conducted by the social network itself, revealed how the company is able to monitor posts and photos in real time to determine when young people feel ‘stressed’, ‘defeated’, ‘overwhelmed’, ‘anxious’, ‘nervous’, ‘stupid’, ‘silly’, ‘useless’, and ‘a failure’.

Capitalising on our emotional pain or discomfort, companies use this knowledge to deliver small dopamine hits directing us from distraction to distraction until we end up in what Kate Moran and Kim Salazar, in a 2018 article, describe as “the Vortex”. “The Vortex is a user-behavior pattern that begins with a single intentional interaction followed by a series of unplanned interactions. This unplanned chain of interactions creates a sense of being “pulled” deeper into the digital space, making the user feel out of control.”

%20(1).png)

According to the Turkish sociologist and writer Zeynep Tufekci, this business model’s success depends on taking advantage of common human weaknesses. “We are particularly susceptible to glimmers of novelty, messages of affirmation and belonging, and messages of outrage toward perceived enemies. These kinds of messages are to the human community what salt, sugar, and fat are to the human appetite.”

I am reminded of the marshmallow experiment where children are told they will be rewarded with another marshmallow if they refrain from eating the first one sitting on the table while the researcher leaves the room. Instead of one marshmallow, we are now surrounded by an endless variety of psychological ‘treats’. In addition, in a world that is becoming increasingly divided and lonely, more often than not we are left to face difficult emotions on our own. The researcher has left the room indefinitely and there are no longer any incentives for restraint.

The light of attention

Someone with an insider eye on the workings of these seduction methods is former Google strategist turned tech philosopher, James Williams. In his 2018 book Stand Out of Our Light: Freedom and Resistance in the Attention Economy he argues that we are, both individually and collectively, facing a crisis of self-regulation. Surrounded by “ubiquitous industrialised, intelligent and in many cases, adversarial types of persuasion” we are redirected from our own goals towards corporate goals of profit generation. “I don’t think it is hyperbole to say that the digital attention economy is the largest and most effective system for human attitudinal and behavioural manipulation the world has ever seen.” He distinguishes three ‘lights of attention’ that are undermined by the attention economy’s distraction machines: spotlight, starlight, and daylight.

The spotlight of attention enables us to focus on our immediate goals: writing an email, tidying up the house, taking care of a friend. When we get interrupted by online notifications or distracted by an advert, we fracture this form of attention. A study conducted at the University of California, Irving indicated that it takes, on average, 23 minutes to refocus. Due to the frequency of distractions, some of us in fact never reach a deep form of attention.

Starlight shines on our medium-term goals, such as learning an instrument, improving our health, or completing a project. With average social media use at over two hours a day, one can only imagine the range of thwarted achievements.

Finally, daylight supports us to “want what we want to want”. This is the light of our values and long-term goals. Williams warns that undermining our daylight may be the most serious and unnoticed danger of the attention economy. “When our daylight is compromised, epistemic distraction results. Epistemic distraction is the diminishment of underlying capacities that allow a person to define or pursue their goals: capacities essential for democracy such as reflection, memory, prediction, leisure, reasoning and goal setting.”

An internal locus of control gives us the sense that we can influence the world around us. But as our ability to pay attention degrades, we are less able to achieve our goals and feel less able to influence the world; this increases our anxiety levels, which in turn degrades our attention.

Williams and many others, such as Johann Hari, author of Stolen Focus – Why You Can’t Pay Attention, believe we are now seeing a vicious cycle of distraction leading to a loss of an ‘internal locus of control’. An internal locus of control gives us the sense that we can influence the world around us. But as our ability to pay attention degrades, we are less able to achieve our goals and feel less able to influence the world; this increases our anxiety levels, which in turn degrades our attention.

While Williams sees these effects as unintended consequences of perverse economic incentives, Shoshanna Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019), believes that historic decisions intentionally handed tech companies a licence to steal our personal data with impunity, and that failure to hold them to account imperils the future of our democracies.

An epistemic coup

In a 2021 article for Transcend Media Service, Zuboff describes how, in response to the September 11 attacks, tech companies were given the green light by the CIA in 2003 to “collect everything and hang on to it forever”, offering them unquestioned “surveillance exceptionalism”. Young entrepreneurs such as Google’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg were now in charge of the largest data surveillance infrastructure the world has ever known, with no democratic oversight. They were granted “a licence to steal human experience and render it as proprietary data”, thereby violating our epistemic rights – the right to know about one’s own personal experience, who we share it with and for what purpose.

This began what Zuboff terms a four-stage ‘epistemic coup’. The secret unilateral permission given to data extractors to mine “the virgin forests of our human nature” of stage one, led to a sharp rise in epistemic inequality, a growing gap between what citizens know and what can be known about them – stage two.

What follows in stage three is epistemic chaos. In pursuit of greater and greater advertising revenues corporations are “radically indifferent to meaning, sense, or truth”. Their systems thrive on epistemic chaos. The more chaos, the more clicks. Brexit, the 2020 US election, and COVID-19 are only a few obvious examples of this epistemic chaos in action.

By weakening public trust in democratic institutions this chaos prepares the ground for the final stage: the institutionalisation of epistemic dominance. By failing to protect their citizens’ epistemic rights, governments lose the trust of their people and choose to exercise further control via already established private surveillance infrastructure. “Democratic governance is displaced by computational governance. The machines know, the systems decide, directed and sustained by the authority of private capital and its absolute technical power”.

In the face of such a colossal attention (and power) grab, what can we do to reclaim what is rightfully ours?

Returning our attention to the world

Professor Yves Citton, in his book The Ecology of Attention (2016), argues that we have paid too much attention to what is in the foreground – facts, figures, what our eyes can see – and proposes that we shift our attention to those elements of life which we hitherto placed in the background: most importantly, our own environment.

It is an illusion to think that the attention economy can exist without the material conditions of a thriving Earth. There has never been a more pressing time to give our full and undivided attention to what is happening to our life support system.

Williams too believes we must give attention to the things that matter and that requires defending our “attentional freedom”. The internet has rapidly become a new social arena, but we have failed to implement adequate systems to enable ethical behaviour and prohibit the rampant attention hijacking we have seen. Our ‘attention ecology’ needs an ethics infrastructure – what Italian philosopher Luciano Floridi terms infraethics – to ensure we protect our capacity to shine our light of attention where we choose.

Zuboff proposes that in this time of epistemic chaos we must “create order together”, in the form of laws, rights, and policies. Instead of arguing downstream about the details of the data property contract, we need to go upstream and declare that the property contract is illegitimate and start outlawing the massive scale extraction of human experience.

It is not too late to listen to our philosophers.

Let’s return to Simone Weil. “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love. Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer. If we turn our mind toward the good, it is impossible that little by little the whole soul will not be attracted thereto in spite of itself.”

We can collectively reclaim the daylight of our attention, our right to decide what matters and what we wish to tend to. We do this every time we offer someone our full undivided attention, every time that we decide to consciously tend to a person or thing that really matters. This “rarest and purest form of generosity” is our birth right and it is our duty to future generations to salvage and protect it. Or in the words of Johann Hari: “We are free citizens of the world, we own our own minds and we can take them back from the motherf***rs who have stolen them”.

∞

Inez Aponte is a facilitator, educator and Human Scale Development consultant. She is co-founder of Crazy Beautiful World CIC, empowering young people to shape their futures with wisdom and compassion.