Algerian social entrepreneurship is taking off at a time of increased government support of startups – but social ventures need clearer recognition and advantages to survive in a “jungle” of for-profit competitors.

Social enterprises have surged in number in Algeria over the past three years, against a background of growing government support for startups, a new report shows.

The first mapping of the social enterprise ecosystem in Algeria, commissioned by the British Council and conducted by Algerian consultancy firm BH Advisory and Social Enterprise UK, State of Social Enterprise in Algeria, was launched in capital city Algiers on 14 December 2021 in front of an audience of social entrepreneurs, several Algerian government ministers and the UK ambassador.

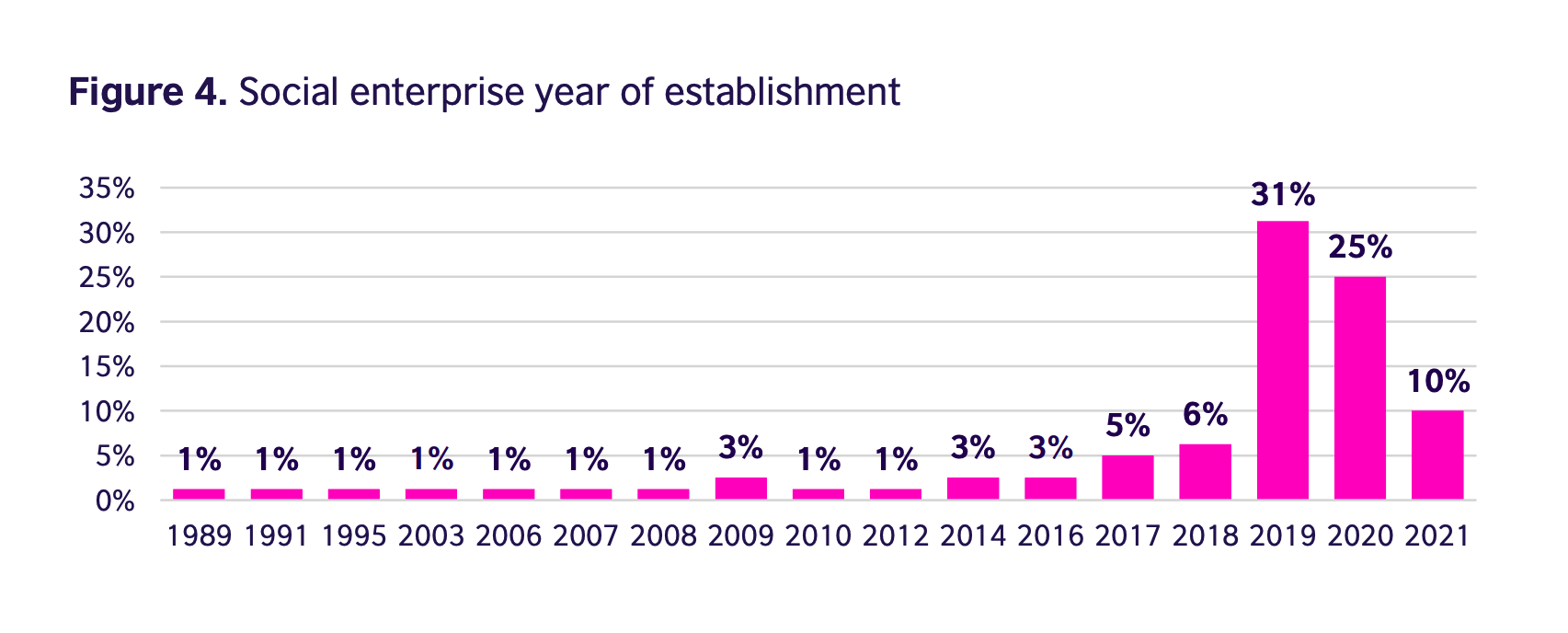

The research shows that 66% of the 80 social enterprises surveyed report having founded their business since 2019.

- Explore the latest facts and figures about social enterprise around the world

The survey builds on 2016 findings from the Euro-Mediterranean Network of Social Economy which estimated that there were more than 7,700 social enterprises in Algeria. This included farmer co-operatives, mutual societies, associations and various other organisations, including small businesses.

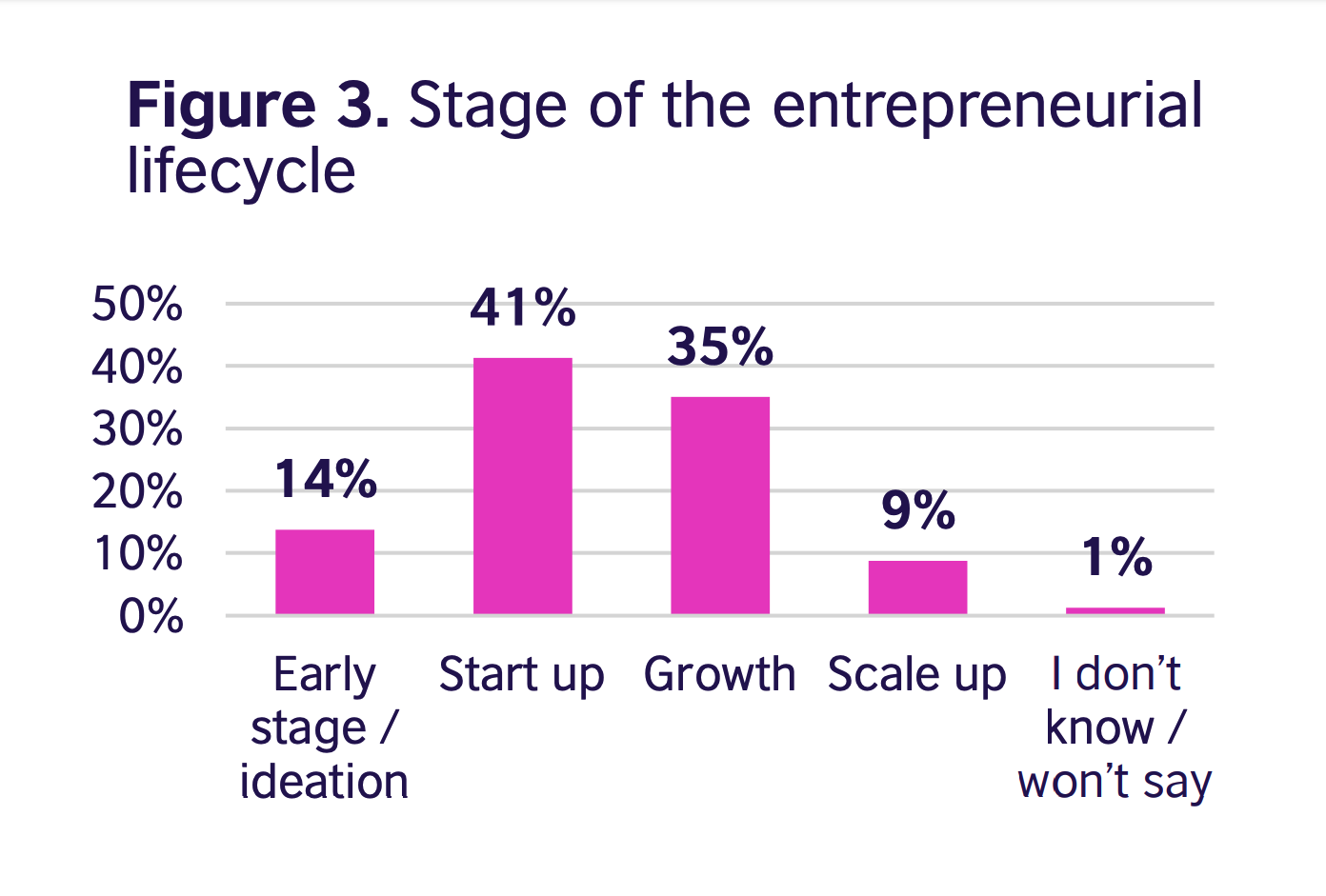

Three quarters of social entrepreneurs report their business is in the early stages of development, and social enterprises are also overwhelmingly led by young people, with 84% of leaders under 45 years old.

“This is a youth-led movement,” says Juliet Cornford, senior researcher at the British Council. “They are passionate about change, and they want to combine changemaking with profitability.”

Above: two-thirds of social enterprises in Algeria have been founded in the past three years (source: British Council)

This recent momentum comes as government support for start-ups of all kinds has increased in Algeria. The current government was elected in 2019 after the resignation of Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the country’s president for 20 years, taking over a country with an economy weakened by oil crises and a 12% unemployment rate.

In September 2020, the ministry for the knowledge economy and startups created a certification label for start-ups, incubators and innovative projects to encourage enterprise creation. Companies that achieve certification enjoy tax incentives and some VAT exemptions, and benefit from funding from the Start-up Investment Fund, a DZD1.2bn (£6.5m) fund created by the government to facilitate access to funding, plus zero-interest loans.

Mr Yacine Oualid, who is Algeria’s minister for startups and the knowledge economy, tells Pioneers Post social enterprises are inherently related to innovation. “Innovation is not only technological. Even though nowadays many startups are closely related to tech, innovation can also come from the impact that an enterprise can have to solve social and environmental problems… This is something that we encourage as a ministry.”

He adds the country’s efforts towards sustainable development need a “huge effort” in terms of innovation, research and development. Social enterprises, in this regard, are “truly bringing new blood” he says.

Among the 142 enterprises and 90 projects that have received the label since 2020, 12% of start-ups and a third of innovative projects have been identified as ‘socially responsible’ by the ministry – although this government identification doesn’t bring any added benefits.

Above: 20% of social enterprises surveyed work in the arts and crafts sectors

Need for more support

While social enterprises in Algeria benefit from existing state support for startups and SMEs generally, the fact that there is no legal distinction between a standard for-profit company and a purpose-led business means they do not benefit from specific preferential support, the study shows.

“The current legal framework does not encourage the creation of social enterprises,” the report says.

The wider support ecosystem for social enterprises – which includes training, incubators, mentoring and financing – is starting to develop, but is, so far, described as insufficient by social entrepreneurs. In practice, only a third of respondents say they have received any type of support.

Above: social enterprises in Algeria tend to be in early stages of development (source: British Council)

The report recommends the creation of a special status for social enterprises, but Mr Oualid, without ruling it out, says policymakers always face a difficult choice when deciding whether or not to create a new legal status, as there is a risk to add another administrative layer that can end up being detrimental.

Government regulations and administrative burdens are described as “significant barriers” to their activities by almost half of the Algerian social entrepreneurs surveyed. Mr Oualid, who founded several businesses himself before taking his ministerial position last year, says issues with over-burdening paperwork have been an obstacle to entrepreneurship generally and not only among social enterprises.

Current entrepreneurship figures “do not reflect Algerian ambition”, despite an increase among young founders, he says, something that the government is seeking to address, for example by enabling people to register companies online.

Surviving in a jungle

The report also shows 59% of social entrepreneurs surveyed struggle to access finance and most have to use their own money to launch their enterprises. More than a quarter say revenue and profitability requirements for bank loans are a barrier, and the same proportion complain about a limited supply of capital. Access to investors due to a limited network is mentioned as a barrier by 34% of respondents.

In a free-market economy, being a social entrepreneur is like being in the middle of a jungle

“In a free-market economy, being a social entrepreneur is like being in the middle of a jungle. It’s very difficult for them to stand out in a market where people only think about returns,” the minister says.

“In Algeria like elsewhere in the world, I think governments have a big role to play,” he says. He adds that governments can provide subsidies at the startup stage. However, there is also a role for private investors to provide seed funding for social entrepreneurs.

Supporting incubators is also a way forward, as training and mentoring are key to helping social entrepreneurs develop their business model so they can be sustainable “from the start”, the minister says.

Above: the Algerian minister for startups and the knowledge economy, Yacine Oualid, at the report launch

A centuries-old culture

Social entrepreneurs in Algeria operate in a variety of sectors, including arts and crafts (20%), culture and leisure (8%) and environment (8%). Ilhem Bouadjimi founded Sac à Tours, an eco-tourism social enterprise that organises trips to rural areas with a mission to promote local heritage and craftsmanship, in 2017.

Improving women’s employability is at the heart of Sac à Tours’ mission. A big part of its work is training local women with the skills needed in the tourism sector, which isn’t developed in rural Algeria, and developing traditional arts and crafts. Since its inception, the social enterprise has brought 200 travellers to 10 regions of the country.

The social side of Algerians is truly cultural. Social entrepreneurship fits Algerian culture perfectly

As tourism was badly hit by the crisis, Bouadjimi successfully pivoted her business: the social enterprise developed new guided cycling tours of Algiers – offering an alternative view of the city, where guided tours are often limited to short walks in the Kasbah, the city’s historical centre.

“It’s about diversifying our offering,” says Bouadjimi. “And simply thinking: why not?” The bicycle project has been a success and balanced the losses experienced by the company in the rest of its activities.

Above: Sac à Tours now offers an alternative way of dicovering Algiers

The concept of social enterprise is fairly new in Algeria – to the point that more than a third of surveyed social entrepreneurs hadn’t heard of the specific concept of social enterprise – despite their own activities fulfilling the criteria of a social enterprise, according to the report. But the practice of business with purpose has in fact been part of Algerian culture for centuries.

The principles of solidarity and mutual aid are deeply rooted in Algerian traditions, the report says, which fostered the emergence of social enterprises. Mr Oualid points out as an example that the concept of “crowdfunding”, which took off in the digital era, has been commonplace in Algerian villages for centuries.

“The social side of Algerians is truly cultural,” the minister says. “Social entrepreneurship fits Algerian culture perfectly.”

Top picture: Ilhem Bouadjimi founded Sac à Tours in 2017. The social enterprise organises trips to rural Algeria, where it trains local women to work in the tourism industry