written by

Kelly Bewers and Dan Woolley

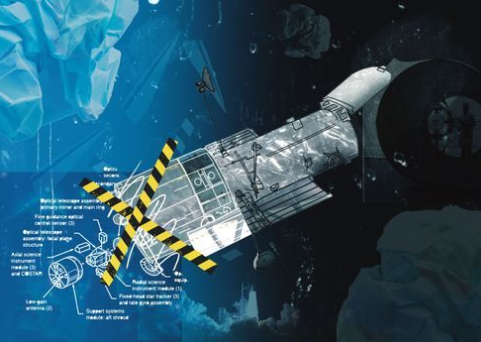

illustration by Heather Savage

The Hubble Telescope, one of the most incredible inventions in our recent times, was designed with failure in mind. Kathryn Sullivan, one of the astronauts onboard Hubble, explains in her brilliant book Handprints on Hubble: An Astronaut’s Story of Invention (2019), how the engineers and inventors accepted that many of its components would be defunct and ultimately replaced by more effective solutions. The NASA team were humble in their belief (and hope) that future generations would improve on their efforts. This acceptance of ‘failure’ as an intrinsic and inevitable evolution of growth, development, and learning enabled the team to create an incredible machine that could be maintained long into the future.

It’s hard to imagine a more complex feat of human engineering, collaboration, and systems design than sending a telescope like Hubble into orbit. If institutions like NASA can accept and, more importantly, design for and learn from failure, then surely we could apply the same thinking to our social, environmental, and economic issues.

Unfortunately, anyone casting an eye over the third sector – both its constituent charities and social enterprises, and the institutions (primarily funders) that prop up the ecosystem – will struggle in vain to find any evidence of failure, let alone associated learnings. This is not the fault of any individual organisation; rather it’s a cultural problem, whose roots are long and deep.

Instigating a culture that foregrounds failure isn’t radical, it’s logical. If those working in social change organisations can feel released from the burdens and constraints of unhelpful performance indicators and have permission to innovate – grounded in the insight, evidence, and learning from the communities and lived experience of those who use services and need care – then change might emerge more quickly and more effectively.

Kyle Zimmer, award-winning social entrepreneur and founder of First Book, goes so far as to say that “the lack of transparency regarding failure in the sector destroys this critical link between innovation and scaling and undercuts the entire sector. This often means that flawed strategies are replicated and iterative improvements are delayed. This defeat for the social sector has profound consequences for the resolution of issues around the world.”

In this article we’re going to share a proposal that foregrounds failure. It contains four key elements, which we have grouped together in a helpful, easy-to-remember acronym: FAIL.

F: Funders

We need to foster a culture of transparency around failure. For the third sector organisations who rely on continual funding, this won’t be an easy transition to make. But what if the organisations that provided the funding – the Charitable Trusts and Foundations, The National Lottery Community Fund, and others – took the first step? There is an opportunity here for these relatively powerful organisations to lead by example.

There are many who would argue that the existing ‘funding model’ is already fractured, faltering and, in many respects, failing. Fortunately, there are some signs of progress. The slow emergence of Participatory Grantmaking, for example, seeks to address the unrepresentative balance of power that is cemented into many charitable foundations, whereby the decision-makers (staff and/or trustees) are often entirely removed from the lives and challenges of those to whom they award – or decline – funding.

Another significant challenge throughout the sector is risk aversion, which is increasingly problematic in the face of urgent problems such as climate change. Charitable Foundations, it might be said, are moving at a glacial pace in a time when the glaciers themselves are disappearing.

Again, there are some signs of progress. In July of this year, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) brought together a range of funders and philanthropists from around the world at their New Frontiers conference, which aimed to “[push] the boundaries of philanthropy and investment … and reflect on the scale of the challenges we face”. As Sophia Parker, JRF’s Director of Emerging Futures wrote in her reflections on the event: “The greatest risk of all is doing too little, or not trying anything new at all. How can we re-weight what counts as ‘risk’ so that inaction is seen as more risky than action?”

By definition, taking risks means accepting, from the outset, the possibility of failure. And that’s ok. But we can do better – far from simply ‘accepting’ unsuccessful outcomes, we can design the architecture of a new system: one that captures, shares, and learns from our respective failures.

A: Assess

Any third sector organisation that wishes to apply for grant funding will encounter at least two hurdles. The first is the funder’s eligibility criteria. The second is the application process. (There is an entirely separate set of challenges regarding those Foundations that do not accept unsolicited applications).

While some level of eligibility criteria will always be necessary, in many cases these criteria are unduly, and often illogically, restrictive. Why do so many Foundations only fund ‘registered charities’? This is a good example of where co-operatives and community businesses, in their various forms, are both misunderstood and overlooked. If a Foundation’s priority is to ensure against private gain or profit, there are other ways to do this – by providing a restricted grant, for instance. Moreover, it should be noted that many co-operatives and community businesses, though not registered charities, operate as non-profits (through asset locks).

Where funders do support a wider range of organisations, this isn’t always clear in the way their eligibility criteria is presented. Opacity is itself a kind of obstacle.

Provided the eligibility hurdle can be cleared, the next step is usually to submit an application. Almost all funders use what is essentially an ‘assessment framework’ – a set of criteria against which applications (for funding) are assessed – though there is considerable variation in how these work and the degree to which they are formalised or codified. This is where the taboo around failure becomes at best unhelpful, and more often counterproductive.

Not uncommonly, funders will look for evidence of previous relevant experience. This is not unreasonable. The problem arises because, intentionally or otherwise, ‘experience’ tends to stand (or be interpreted) as a proxy for ‘success’. And so failure – which is often the more interesting element of experience, and almost always the more instructive – is swept under the carpet.

Philanthropist and funder Rohini Nilekani describes the pivotal role that funding plays in repressing stories of failure: “Funding is so closely tied to the vision of success that social organisations are forced to find ways to claim success, not necessarily [to achieve] societal outcomes but for continuity of funding.”

But what if funders explicitly changed their assessment frameworks to recognise and reward experience gained and lessons learned through failure? Such a change might bring at least two benefits.

First, it would create a ‘safe space’ for applicants to foreground past failures and mistakes. What went wrong? What can be learned? How would these learnings inform a different approach this time around?

Second, it would create, from the outset, an honest and open dialogue between the funder and the applicant/grantee. Whereas, truth be told, the current system is more akin to a game of Cat and Mouse.

I: Impact

If Assessment Frameworks are the gatekeeper at the start of the funding process, their counterpart can be found towards the end, in the project Evaluation phase.

Here we encounter the same problem, only magnified: the need to evidence success, with little room left for learnings of any kind, let alone those that can be drawn from failure.

The issue is made worse by the fact that, in the funding world, Evaluation has come to be dominated by Impact Measurement Frameworks (three words that could bring any sane person to their knees) which are geared towards metrics; any nuances must therefore be sawn off, chiselled away, and sanded down, if the complex shape of a project is to be banged into the square hole of quantification.

These two problems – the expectations of success and the focus on metrics – sustain and reinforce one another. Because ultimately, in the reductive world of impact measurement, it all boils down to a simple, colourful graph – one that tracks nicely upwards, untroubled by the complexities of real experience.

So what can be done differently? As one of the authors of this piece has argued elsewhere:

“Fixation on measurement distracts from the important work of bettering. The language of outputs is reductive. What happens after the ‘outcome’ – someone getting a job or moving out of temporary accommodation? These ‘results’ aren’t an end state. Telling stories, on the other hand, has innate value and is evidence of change. Experience has nuance, beyond what figures and graphs can relay. Stories of experience, carefully curated and thoughtfully told, are more powerful ways to evidence value and, importantly, learn, but it’s harder to do. And a story doesn’t fit neatly into a graph.”

The first step, then, is away from PowerPoint and into reality: fewer metrics, more stories. But not the kind of stories you find in low-rent Hollywood films, where heroes are ever victorious and happy endings guaranteed. Instead we need grown-up stories, with all the nuance, imperfection, and three-dimensional characters that we find in real life.

L: Learning

Failure in itself is not valuable unless we create the conditions and culture around it to build learning. This requires intentional, proactive commitment and design.

The complexity of the challenges we face – from social injustice to climate breakdown and beyond – can seem unfathomable. If they were easy to solve then wouldn’t the state (or the market) have already delivered the solutions? We can’t apply conventional economic principles of value (profit, speed, growth) to the structural inequality of social care or the decreasing biodiversity of our land. Surely the only way to move forward is to experiment, test, learn, fail and try again.

The development and sharing of case studies has become synonymous with ‘best practice use cases’ or ‘success stories’: curated examples of projects or solutions that worked. Yet the definition of a ‘case study’ isn’t limited to those stories that ended in success – it should also include those that didn’t work. But where are these stories in the discourse of the social impact sector?

Split Banana is a social enterprise that exists to reshape Relationships and Sex education in schools by delivering workshops with young people. It was founded in response to the inadequate formal sex education curriculum delivered in UK schools, which hadn’t changed for over twenty years and did not contain any content regarding consent, LGBTQ+ relationships, pornography or body image. As a creative way to start addressing this failure in the education system, Split Banana developed an open source, anonymous storytelling platform for people to share their experiences of sex education – “good, bad or non-existent.” Whilst the purpose isn’t to celebrate failure, it does create a safe space for people to learn from each other’s experiences, understand that they are not alone when it comes to having received poor sex education and also brings a bit of humour to a subject that can often feel shameful, embarrassing or stigmatising.

Examples like this show us that we can talk about and learn from failure in a fun and accessible way that promotes collective learning rather than individual shaming.

We’re issuing a call to action for funders: let’s change the narrative. We’re looking for support to build an “anti-case study” platform. An open-source and searchable online tool that showcases the unsuccess stories. We can learn from the failures and mistakes of our peers and collectively uplift the knowledge base of our sector.

This is the first opportunity for funders to take the lead: partnering with us to build the platform. The second opportunity – and the challenge – is to normalise the sharing of failure. To do that, we need to go beyond providing a platform. We need to fundamentally change the frameworks that govern the grant-funding process.

Solutions are found by people willing to experiment

In this article we’ve taken a robust look at the culture around some of the current funding, impact measurement, and assessment approaches that dominate the social and economic impact sector. But as well as taking a critical view, we want to be propositional, not oppositional.

Calling for funders to support the anti-case study platform isn’t enough on its own. We’re going to start telling the stories of failure today, right now and invite readers and supporters to do the same. This simple act of individual sharing can contribute to a library of failure anecdotes that can lift our collective knowledge.

As with the Hubble telescope, where we took our inspiration for foregrounding failure, economist Mariana Mazzucato also references NASA’s approach to space exploration in her book Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism (2021). Mazzucato argues that: “Solutions are found by people willing to participate and experiment … not by picking supposedly good solutions in advance and trying to make them work.”

If funders apply the same principle to creating social change, we could find that candid, practical accounts of where and how projects didn’t work will inspire new experiments that might. ∞

Kelly Bewers is an independent consultant, strategist and facilitator working with organisations that are designing new, more equitable systems of social and economic justice.

Dan Woolley is Stir to Action’s Head of Fundraising. He has previously worked for a range of charities and social enterprises, focusing on issues affecting environment, community, alternative economics and social mobility.